The Decline of American Institutions

The American identity is unique both historically speaking and across the modern globe. What is perhaps most unique about Americans is our extreme fondness for political institutions. In the early days of the American Revolution, it is widely known that the patriots and moderate colonial citizens opposed burdensome taxation by the British crown. While this is mostly true, it misses the most important point: the American colonists were more upset about the lack of representation in parliament than they were about the taxation itself. In 18th century England, it was well established that taxation was not a right of the king. Instead, taxation was a gift, freely given by the people, through the authority of their representative in parliament. This doctrine was well established through the Magna Carta, which restricted the sovereign power of the monarch. When King George III attempted to raise revenue on the American colonists without representation in parliament, the colonists felt that he had trampled on the sovereignty of both the Magna Carta and the institution of parliament as they could not freely give the gift of taxation without a representative through which to do so. Contrary to popular belief, the early colonists did not want independence from Britain. Instead, they wanted reconciliation with the crown and to be recognized under the established governmental institutions of the time. In other words, there was a proper and well-established way to do things, and the form of taxation used by the crown was considered unconstitutional.

It may be hard for modern audiences to understand, but reverence for political institutions is not the norm either historically or globally. In most places around the world, both now and then, power is concentrated typically within one individual or one party. This individual or party wields sole authority, typically through violence and coercion, with no abstract legal or cultural expectations with which to rein them in. Some notable examples include Saddam Hussein's rule in Iraq, Kim Jong UN's iron fist in North Korea, Joseph Stalin’s genocidal communist dictators ship in Soviet Russia, and even XI Jinping’s rule in China. Syria, Rwanda, Vietnam, Venezuela, and numerous other places across the globe claim to follow established political institutions, but this is just for show. In reality, political authority is derived from those who already maintain vast amounts of power. In many of these places, elections are a sham and court cases only maintain authority if those in power agree with the outcome of the case. The American experience of putting our entire faith in our institutions, rather than party, individual, family, or clan/ethnicity is quite unique.

As stated earlier, when the crown ignored both parliament and the Magna Carta, the early colonists were enraged and sought to form their own institutions. In September 1774, representatives from each colony met together at the first Continental Congress. In this Congress, many proposed solutions to the unconstitutional actions of the British crown were proposed. These included a boycott of British goods, the establishment of regularly drilled militias, a redress of grievances, and a petition to the king to address those grievances. One of the most notable examples of this Congress was the proposed establishment of a Continental Association. This association was intended to be a political institution that included representatives from every colony. It would help the colonies organize, share information, facilitate trade, mutual defense, and more. If this sounds familiar, it should. Just as the Magna Carta provided the bones for the modern-day American constitution, so too did the first Continental Congress provide the bones for the United States Congress. While the Continental Association was not ultimately established in 1774, it did prove to be useful. After hostilities broke out in Lexington and Concord just six months later, a second Continental Congress was convened. This second Continental Congress would declare independence from Great Britain through what was called the Lee resolution, formally adopted as the Declaration of Independence.

The reason that this is important is because it shows an immense aptitude for understanding the role and importance of a political institution rather than mob mentality. The early colonists did not find a warlord to rally behind without any clear attainable goals, organization, or strategy. Likewise, they did not simply devolve into family or clan identities, and the states did not fracture from one another, even when Great Britain threatened to shut down the port in Boston. The American colonists did everything they could to ensure that all political decisions and power were placed into an organized institution which could be monitored and participated in by those qualified to do so. Without this level of organization, America as we know it today would not exist.

Following the Revolutionary War, the United States engaged in a decades long debate about what the role of federal and state governments should be. The articles of confederation, which had governed the United States from 1777 to 1786, had been deemed too weak and inefficient to remain in place. A new framework for the federal government was needed. A pressing issue was that many states with a small population wanted every state to have equal representation in the legislature. States with a larger population, such as Virginia, wanted representation in the legislature to be based on state population. Rather than going to war or redrawing state boundaries, the colonists spent four months virtually locked in a building hashing out the details of what this new government would look like. Ultimately, this convention would lead to the modern government we know today: A constitution that clearly delineates the separate branches of government and the checks that each one has on the other, a Bill of Rights that protects individuals and states’ rights, and clear, procedural expectations of how all functions of government are intended to work.

We must understand how crucially important this framework is to understand the second half of this article. As Americans, we place (or used to) all of our faith in these these institutions and that they are working correctly and efficiently for the best possible outcome for all Americans. It is, or was, widely understood that, for example, members of Congress on a committee would have expertise within that committee. Justices on the Supreme Court were more knowledgeable than the average American, and that their opinion should be trusted. That the president represented the general will of the people, and that his decisions should be accepted whether one liked them or not. What this underscores is trust in an institution that gives the institution validity. This trust is what might also be called a social contract. Similar to Thomas Hobbe's leviathan, a political institution can only operate effectively through the consent of the governed. The trust by the general public that these institutions are functioning as intended is, by definition, consent of the governed to be governed. So what happens when this trust disappears?

In 2025, we have seen shocking statistics about the general public's perception of our institutions. According to a Gallup poll, current congressional approval ratings have declined to about 23% since peaking around 85% in 2001. In 2001, 63% of Americans approved of how the Supreme Court was doing its job compared to 44% today. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and both Bush Senior and Junior enjoyed presidential approval ratings of 80% or higher, compared to president Trump's approval rating today of roughly 37%. In short, faith in these institutions is eroding. Unfortunately, it's easy to see why.

Congress maintains the power of the purse and funds all actions undertaken by the federal government. The last time that congress passed all eight appropriation bills by October 1st, which is the start of the fiscal year, was in 1996. Yes, it has been almost 30 years since Congress has successfully enacted one of its core constitutional priorities on time. This should really come as no surprise as Congress remains bitter and divided, reflecting the current national sentiment. In the 116th and 117th Congress, both controlled by Nancy Pelosi and her Democrat allies, political debate was completely stifled. The house Rules Committee granted no open rules, no modified open rules, 59 structured rules, and 89 closed rules for the consideration of bills and resolutions. What this meant is that House Republicans were not allowed to engage in open debate or offer amendments to bills brought to the floor of the House of Representatives. In the 118th Congress, this process has been slightly improved. The Republican-held Rules Committee has stated ““In the 118th Congress, House Republicans provided a more than 40 percent increase in the number of rules with amendments as compared to either of the previous two Congresses under Democrat control, considered more amendments on the floor than the previous four years combined, and considered a modified-open rule [section 5 of H.Res. 5, 118th Congress] for the first time in over three Congresses. Nearly 1,600 amendments were offered to a single bill, a massive increase from any other bill in recent memory.”

In the House of Representatives, the number of bills introduced has fallen from a peak of 22,000 In 1970 to a paltry 9000 in 2022. Correspondingly, the number of bills introduced per member has also fallen from 50 to 22. For advocates of small government, this may seem like a win. For those who would like to see the legislature legislate, it may contribute to low approval ratings. Most tellingly is the ratio of bills passed out of the House; In 1950, 23% of bills introduced were passed. In 2022, only 9% were passed. In 1973, there were almost 6,000 committee and subcommittee hearings. By 2022, that number had fallen to 1700.

The Senate is no better. The upper chamber also maintains a roughly 9% passage rate of bills introduced, in tandem with the hours spent (on average) in session falling from 8 to 5.5. These statistics do not count bills passed by the House that are not taken up by the Senate where they languish and die.

From 1900 to the election of Richard Nixon in 1968, the U.S. had a divided government only 20 percent of the time. From Nixon through Trump's first term, it was divided 69 percent of the time. The estimated probability of a divided government heading into the 2020 election was 78 percent, the highest in the past century, up until the 2025 election.

Because of Congressional gridlock, the White House is routinely forced to step into the role of legislator. While the number of executive orders has stayed relatively stable for the last fifty years, the boomerang effect between competing administrations can be seen in executive orders that are put in place within the first one hundred days of a new presidency. These orders are intended to undo unfavorable practices of a previous administration. The number of executive orders emplaced in the first one hundred days of a new presidency has increased exponentially since President Trump's first term. Likewise, Congress has even taken up White House proposals as legislation. The Builder Act, introduced in the 116th Congress, was a non-newsworthy set of very important changes to the national Environmental Protection Act that were originally proposed as a set of administration rules implemented under the Council on Environmental Quality. Legislation that goes from the White House to Congress, rather than the other way around, shows that the institutions are not working as intended.

Politicization has also come to the Supreme Court. In 2022, Only 29% of the supreme court's decisions were unanimous, down from a peak of 43% in the previous decade. Previously, the most common vote alignment was 9 - 0. However, beginning in this term, the most common alignment became 6 - 3, following party lines. High-profile cases have also dramatically altered the perception of the Supreme Court. The purpose of the court is to enact strict constitutional checks on the executive branch. It's authority is derived not from opinion, but by textual interpretation of our nation's foundational institutions. Because of this, the general public loses faith in the validity of the court when it changes its stance on fundamental laws. For example, Roe V wade was established in 1973 and became the de facto Position of the United States government, until that position was overturned in 2022. This whiplash effect on American citizens leads them to view the court not as an immovable arbiter of objective justice, but more as an arbitrary or subjective interpreter of the law that can change with time. It is impossible to state how important this erosion of trust is in the validity of the opinions that the court hands down. If people no longer trust the legitimacy of the court, it has no power.

We have spent 2000 words briefly going over hundreds of years of nation building and the modern decline of the institutions which took so long to build. We must now discuss the implication of this decline. When Americans no longer feel that these institutions are enacting the general will of the people, they will resort to other means to enact what they believe is best for the nation. For example, when the legislators cease to legislate, the executive branch is forced to step in and take on the mantle of both. While this has not yet begun in the United States, extreme examples of this do exist elsewhere in the world. This is how Napoleon gained power, as well as Stalin and Julius Caesar. The American people demand that their government is responsive to their needs. The legislature is the primary vehicle to respond to these needs; if it is unable to fulfill this role, the people will look to a strong man who will step in and break the gridlock and paralysis which has kept the institution from fulfilling its obligations. The health and independence of a legislature is paramount to prevent this.

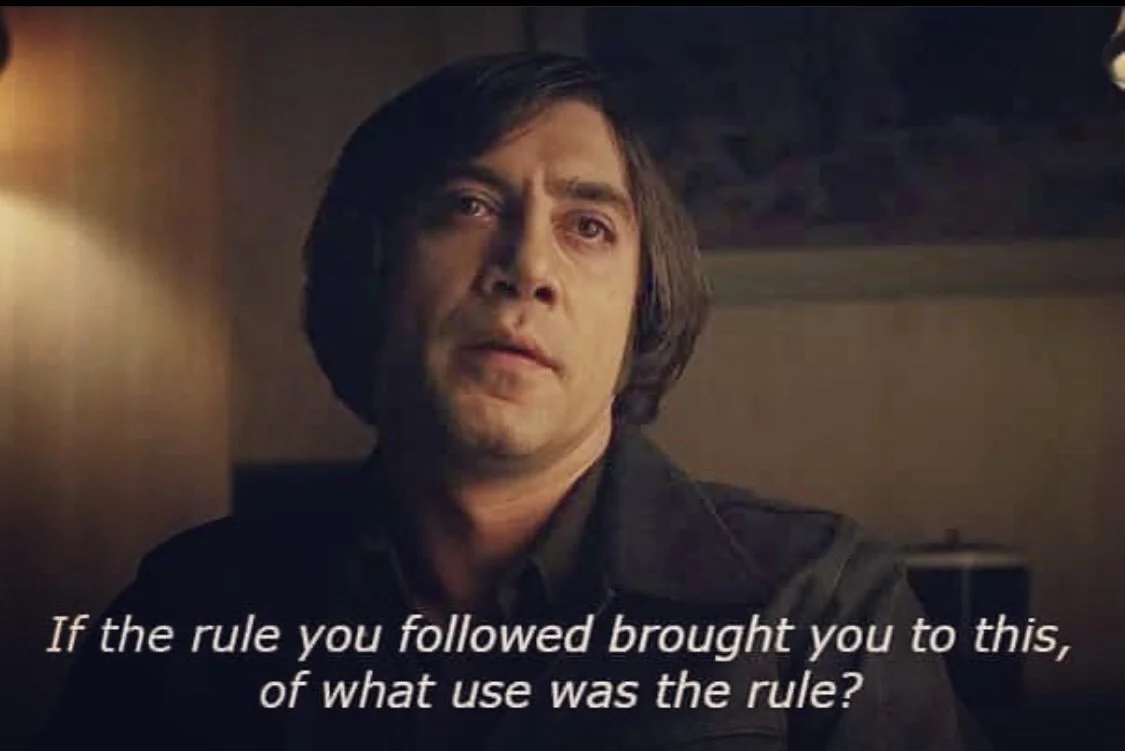

A poignant question from No Country for Old Men

Likewise, the courts must retain their validity. If courts make decisions which the people feel are arbitrary or not based on an unmovable set of principles, such as the Constitution, their holdings will not be enforced. Without the rule of law, the executive branch gains the ability to act with impunity, which is exactly what the revolutionaries feared in the first paragraph of this article. Therefore, the courts must only be able to make legal decisions set within a specific and enumerated set of parameters. Without this robust, unchanging document, all decisions will appear arbitrary or subjective and therefore invalid.

The ultimate threat from the dissolution of our institutions is a retreat from what has made us great and prosperous. It is this robust and august set of laws, which every citizen feels that they can participate in and are beholden to, which have made the United States fruitful and, most importantly, stable. If the citizenry feels that they are no longer beholden to the law, they will retreat to more primitive forms of government. Lest you think that this is fear mongering, I would remind you that this is exactly what happened in 1862 when multiple states found that their beliefs were irreconcilable with the United States federal government. This secession ultimately started the civil war, a conflict that still divides our nation today.

Without long term stability, investments cease, loans cease, friction intensifies, balkanization occurs, trade declines, and individual regions we'll stop working together both ideologically, culturally, and economically. More primitive forms of government will arise which place emphasis on things like ethnicity, religion, family, clan, or region. This fractionalization, both literally and politically, threatens to destroy the United States. Abraham Lincoln is perhaps the greatest progenitor of this idea. Despite being known as the great emancipator, Lincoln’s actual motivations had nothing to do with the morality slavery. In a letter to Horace Greeley, he says:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy Slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union, and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

Perhaps Lincoln’s most profound legacy is how important it was to preserve the institution of the American union, even at the cost of nearly one million deaths of his own citizens. Without functioning institutions, our very fabric will be rent apart, and consequences of this are nearly impossible to calculate.